AI革命:超知能への道のり|Wait But Why より (パート1)

本記事では、AI(人工知能)の可能性とその未来について、海外で人気のウェブサイト「waitbutwhy」からの記事をご紹介します。この記事は、2015年に英語で書かれたもので、多くの議論や興味深いコメントが寄せられています。私たちは、この内容を日本語でもお届けしたいと思い、ChatGPTとDeepLを活用して日本語に翻訳しました。waitbutwhyの著者に敬意を表し、彼らのインサイトと独創的な視点を日本の読者にも伝えられることを願っています。

私たちは、地球上に人類が誕生したときに匹敵する変化の瀬戸際にいます。 - バーナー・ビンジ

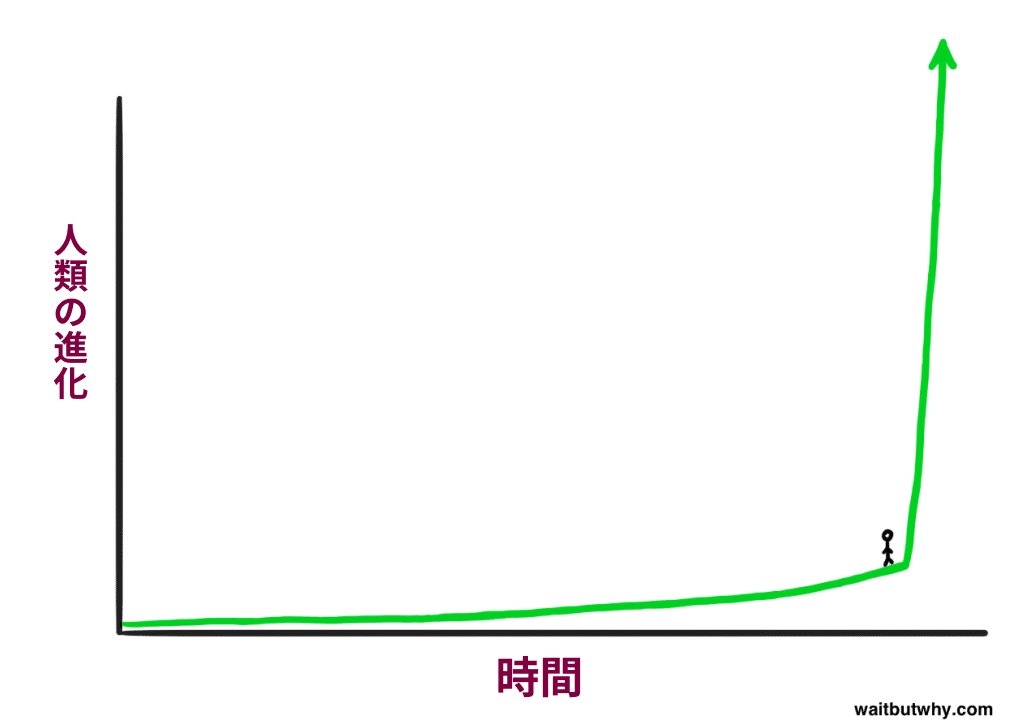

ここに立っているとどんな気分になるでしょうか?

We are on the edge of change comparable to the rise of human life on Earth. — Vernor Vinge

What does it feel like to stand here?

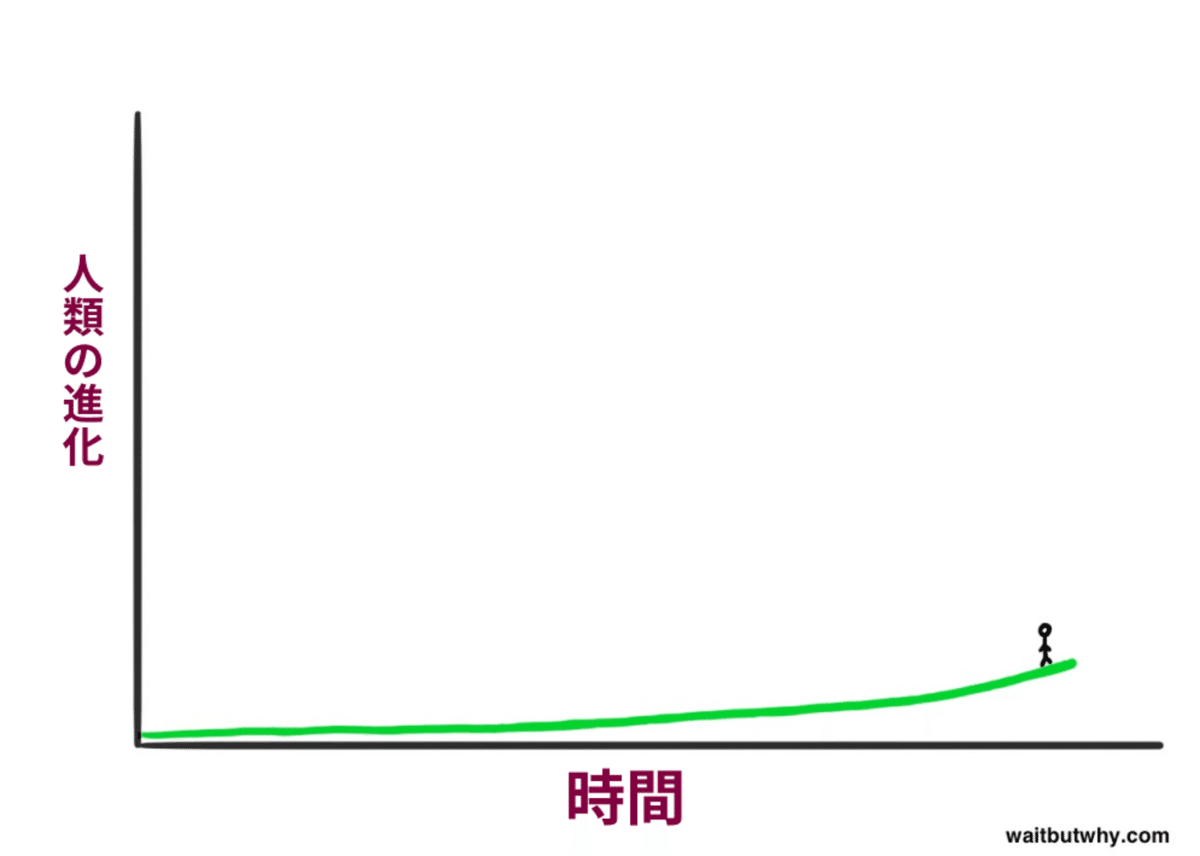

とてもインパクトのある場所に立っているように感じられますが、時間軸のグラフ上に立っているときの感覚について覚えておかなければならないことがあります。それは、自分の右側にあるものが見えないということです。だから、そこに立っている実際の感覚はこんな感じです。

これはおそらくごく普通の感覚でしょう...

It seems like a pretty intense place to be standing—but then you have to remember something about what it’s like to stand on a time graph: you can’t see what’s to your right. So here’s how it actually feels to stand there:

Which probably feels pretty normal…

遥か未来 - もうすぐやってくる

1750年に、タイムマシンで過去に戻ったと想像してみてください。世界が永遠の停電状態で、長距離通信は大声で叫ぶか大砲を空に撃つしかなく、すべての交通機関が干し草で動いていた時代です。そこに着いたら、適当な人物を連れてきて、2015年まで連れて来て、彼を連れ回して、すべてのものに彼がどのように反応するかを見るのです。高速道路を走る光り輝くカプセルを目にし、その日の早い時間に海の反対側にいた人と話をし、1000マイル離れたところで行われているスポーツを見て、50年前に行われた音楽の演奏を聞き、リアルな画像を捉えたり生きた瞬間を記録したりできる魔法の四角い箱で遊んだり、彼がどこにいるかを示す超常現象のような青い点が動く地図を生成したり、相手の顔を見ながら国の反対側にいるのに会話したり、他にも想像を絶する魔法の数々を目の当たりにする彼の気持ちを理解することは、私たちには不可能です。これはすべて、あなたがインターネットを見せたり、国際宇宙ステーション、大型ハドロン衝突型加速器、核兵器、一般相対性理論などについて説明する前の話です。

The Far Future—Coming SoonImagine taking a time machine back to 1750—a time when the world was in a permanent power outage, long-distance communication meant either yelling loudly or firing a cannon in the air, and all transportation ran on hay. When you get there, you retrieve a dude, bring him to 2015, and then walk him around and watch him react to everything. It’s impossible for us to understand what it would be like for him to see shiny capsules racing by on a highway, talk to people who had been on the other side of the ocean earlier in the day, watch sports that were being played 1,000 miles away, hear a musical performance that happened 50 years ago, and play with my magical wizard rectangle that he could use to capture a real-life image or record a living moment, generate a map with a paranormal moving blue dot that shows him where he is, look at someone’s face and chat with them even though they’re on the other side of the country, and worlds of other inconceivable sorcery. This is all before you show him the internet or explain things like the International Space Station, the Large Hadron Collider, nuclear weapons, or general relativity.

彼にとってこの経験は、驚きでも衝撃でもなく、頭がおかしくなるようなものでもないでしょう。それらの言葉は十分な大きさではないのです。実際、彼は死ぬかもしれません。

This experience for him wouldn’t be surprising or shocking or even mind-blowing—those words aren’t big enough. He might actually die.

しかし、面白いことに、もし彼が1750年に戻り、私たちが彼の反応を見られたことに嫉妬して、同じことをしてみたいと思ったとしたら、彼はタイムマシンに乗って同じ距離を戻り、1500年頃の誰かを連れてきて、1750年に連れてきて、すべてを見せるでしょう。そして、1500年の人はたくさんのことに驚くでしょうが、死ぬことはないでしょう。1500年と1750年はとても違いましたが、1750年から2015年ほどの違いはなかったので、彼にとってはそれほど狂気の経験ではないでしょう。1500年の人は、宇宙と物理学についての頭がおかしくなるようなことを学ぶでしょうし、ヨーロッパがその新しい帝国主義のブームにどれだけ熱心になったかに感心するでしょうし、彼の世界地図の概念を大幅に改訂しなければならないでしょう。しかし、1750年の日常生活 - 交通や通信など - を見ても、彼が死ぬことはないでしょう。

But here’s the interesting thing—if he then went back to 1750 and got jealous that we got to see his reaction and decided he wanted to try the same thing, he’d take the time machine and go back the same distance, get someone from around the year 1500, bring him to 1750, and show him everything. And the 1500 guy would be shocked by a lot of things—but he wouldn’t die. It would be far less of an insane experience for him, because while 1500 and 1750 were very different, they were much less different than 1750 to 2015. The 1500 guy would learn some mind-bending shit about space and physics, he’d be impressed with how committed Europe turned out to be with that new imperialism fad, and he’d have to do some major revisions of his world map conception. But watching everyday life go by in 1750—transportation, communication, etc.—definitely wouldn’t make him die.

いいえ、1750年の人が私たちが彼と一緒に楽しんだのと同じくらい楽しむためには、もっと遠くまで遡らなければなりません。おそらく、最初の農業革命が最初の都市と文明の概念を生み出す以前の紀元前12,000年頃までさかのぼる必要があるでしょう。純粋な狩猟採集の世界から来た人、つまり人間がほぼ他の動物種と変わらなかった時代から来た人が、1750年の巨大な人間の帝国、そびえ立つ教会、海を渡る船、「内側」という概念、そして膨大な山のような人類の集合的で蓄積された知識と発見を目にしたら、おそらく死んでしまうでしょう。

No, in order for the 1750 guy to have as much fun as we had with him, he’d have to go much farther back—maybe all the way back to about 12,000 BC, before the First Agricultural Revolution gave rise to the first cities and to the concept of civilization. If someone from a purely hunter-gatherer world—from a time when humans were, more or less, just another animal species—saw the vast human empires of 1750 with their towering churches, their ocean-crossing ships, their concept of being “inside,” and their enormous mountain of collective, accumulated human knowledge and discovery—he’d likely die.

そして、もし彼が死んだ後に嫉妬して同じことをしたいと思ったら、どうでしょう。もし彼が12,000年前の紀元前24,000年に戻り、誰かを連れてきて紀元前12,000年に連れてきたとしたら、その人にすべてを見せても、その人は「で、何が言いたいの?誰が気にするの?」というような反応をするでしょう。紀元前12,000年の人が同じように楽しむためには、10万年以上前に戻って、初めて火や言葉を見せられる人を連れてこなければなりません。

And then what if, after dying, he got jealous and wanted to do the same thing. If he went back 12,000 years to 24,000 BC and got a guy and brought him to 12,000 BC, he’d show the guy everything and the guy would be like, “Okay what’s your point who cares.” For the 12,000 BC guy to have the same fun, he’d have to go back over 100,000 years and get someone he could show fire and language to for the first time.

誰かが未来に運ばれ、経験するショックのレベルで死ぬためには、「死ぬレベルの進歩」、つまり「死の進歩単位(DPU)」が達成されるのに十分な年数が経過していなければなりません。狩猟採集時代のDPUは10万年以上かかりましたが、農業革命後のペースでは約12,000年しかかかりませんでした。産業革命後の世界はとても速いスピードで進んでいるので、1750年の人がDPUを経験するには数百年先に行く必要があるのです。

In order for someone to be transported into the future and die from the level of shock they’d experience, they have to go enough years ahead that a “die level of progress,” or a Die Progress Unit (DPU) has been achieved. So a DPU took over 100,000 years in hunter-gatherer times, but at the post-Agricultural Revolution rate, it only took about 12,000 years. The post-Industrial Revolution world has moved so quickly that a 1750 person only needs to go forward a couple hundred years for a DPU to have happened.

このパターン、つまり時間の経過とともに人類の進歩がどんどん速くなっていくことを、未来学者のレイ・カーツワイルは人類史の「加速する変化の法則」と呼んでいます。これは、より進んだ社会の方が、より進んでいない社会よりも速いペースで進歩する能力があるからです。19世紀の人類は15世紀の人類よりも知識があり、技術も優れていたので、19世紀の人類が15世紀よりもはるかに多くの進歩を遂げたのは当然のことです。15世紀の人類は19世紀の人類の敵ではありませんでした。11← これらを開く

This pattern—human progress moving quicker and quicker as time goes on—is what futurist Ray Kurzweil calls human history’s Law of Accelerating Returns. This happens because more advanced societies have the ability to progress at a faster rate than less advanced societies—because they’re more advanced. 19th century humanity knew more and had better technology than 15th century humanity, so it’s no surprise that humanity made far more advances in the 19th century than in the 15th century—15th century humanity was no match for 19th century humanity.11← open these

これは小さなスケールでも当てはまります。映画「バック・トゥ・ザ・フューチャー」は1985年に公開され、「過去」は1955年に設定されていました。映画の中で、マイケル・J・フォックスが1955年に戻ったとき、テレビの新しさ、ソーダの値段、シュリルな電気ギターへの愛着のなさ、スラングの違いに戸惑いました。確かに別世界でしたが、もし今日この映画が作られ、過去が1985年に設定されていたら、もっと大きな違いでもっと楽しめたはずです。主人公は、パソコン、インターネット、携帯電話のない時代に行くことになります。今日のマーティ・マクフライ、つまり90年代後半に生まれた10代の若者は、映画のマーティ・マクフライが1955年に違和感を覚えたよりも、1985年にずっと違和感を覚えるでしょう。

This works on smaller scales too. The movie Back to the Future came out in 1985, and “the past” took place in 1955. In the movie, when Michael J. Fox went back to 1955, he was caught off-guard by the newness of TVs, the prices of soda, the lack of love for shrill electric guitar, and the variation in slang. It was a different world, yes—but if the movie were made today and the past took place in 1985, the movie could have had much more fun with much bigger differences. The character would be in a time before personal computers, internet, or cell phones—today’s Marty McFly, a teenager born in the late 90s, would be much more out of place in 1985 than the movie’s Marty McFly was in 1955.

これは、先ほど議論したのと同じ理由、つまり「加速する変化の法則」によるものです。1985年から2015年の平均的な進歩率は、1955年から1985年の進歩率よりも高かったのです。なぜなら、前者の方がより進んだ世界だったからです。そのため、直近の30年間の方が、その前の30年間よりもはるかに大きな変化が起こったのです。

This is for the same reason we just discussed—the Law of Accelerating Returns. The average rate of advancement between 1985 and 2015 was higher than the rate between 1955 and 1985—because the former was a more advanced world—so much more change happened in the most recent 30 years than in the prior 30.

つまり、進歩はどんどん大きくなり、どんどん速くなっているのです。このことは、私たちの未来について、かなり激しいことを示唆しているのではないでしょうか?

So—advances are getting bigger and bigger and happening more and more quickly. This suggests some pretty intense things about our future, right?

カーツワイルは、20世紀のすべての進歩が、2000年の進歩速度で達成されるとしたら、わずか20年でできたはずだと示唆しています。言い換えれば、2000年までに、進歩の速度は20世紀の平均進歩速度の5倍になったということです。彼は、2000年から2014年の間に、20世紀分の進歩がもう一度起こり、2021年までにさらに20世紀分の進歩が起こると考えています。数十年後には、20世紀分の進歩が同じ年に何度も起こり、さらにその後は、1ヶ月未満で起こるようになると考えています。つまり、加速する変化の法則により、カーツワイルは21世紀が20世紀の1,000倍の進歩を遂げると考えているのです。

Kurzweil suggests that the progress of the entire 20th century would have been achieved in only 20 years at the rate of advancement in the year 2000—in other words, by 2000, the rate of progress was five times faster than the average rate of progress during the 20th century. He believes another 20th century’s worth of progress happened between 2000 and 2014 and that another 20th century’s worth of progress will happen by 2021, in only seven years. A couple decades later, he believes a 20th century’s worth of progress will happen multiple times in the same year, and even later, in less than one month. All in all, because of the Law of Accelerating Returns, Kurzweil believes that the 21st century will achieve 1,000 times the progress of the 20th century.

もしカーツワイルや彼に同意する他の人たちが正しいとすれば、私たちは2030年には1750年の人が2015年に驚いたのと同じように驚くかもしれません。つまり、次のDPUはほんの数十年しかかからないかもしれません。そして、2050年の世界は今日の世界とあまりにも違いすぎて、私たちはほとんど認識できないかもしれません。

If Kurzweil and others who agree with him are correct, then we may be as blown away by 2030 as our 1750 guy was by 2015—i.e. the next DPU might only take a couple decades—and the world in 2050 might be so vastly different than today’s world that we would barely recognize it.

これはサイエンス・フィクションではありません。多くの科学者が、あなたや私よりも賢く、知識が豊富で、確信を持っていることです。そして、歴史を見れば、論理的に予測すべきことなのです。

This isn’t science fiction. It’s what many scientists smarter and more knowledgeable than you or I firmly believe—and if you look at history, it’s what we should logically predict.

では、なぜ「35年後の世界は全く別物になっているかもしれない」と言われても、「すごい...でもないな」と思ってしまうのでしょうか?私たちが未来の途方もない予測に懐疑的になる3つの理由があります。

So then why, when you hear me say something like “the world 35 years from now might be totally unrecognizable,” are you thinking, “Cool….but nahhhhhhh”? Three reasons we’re skeptical of outlandish forecasts of the future:

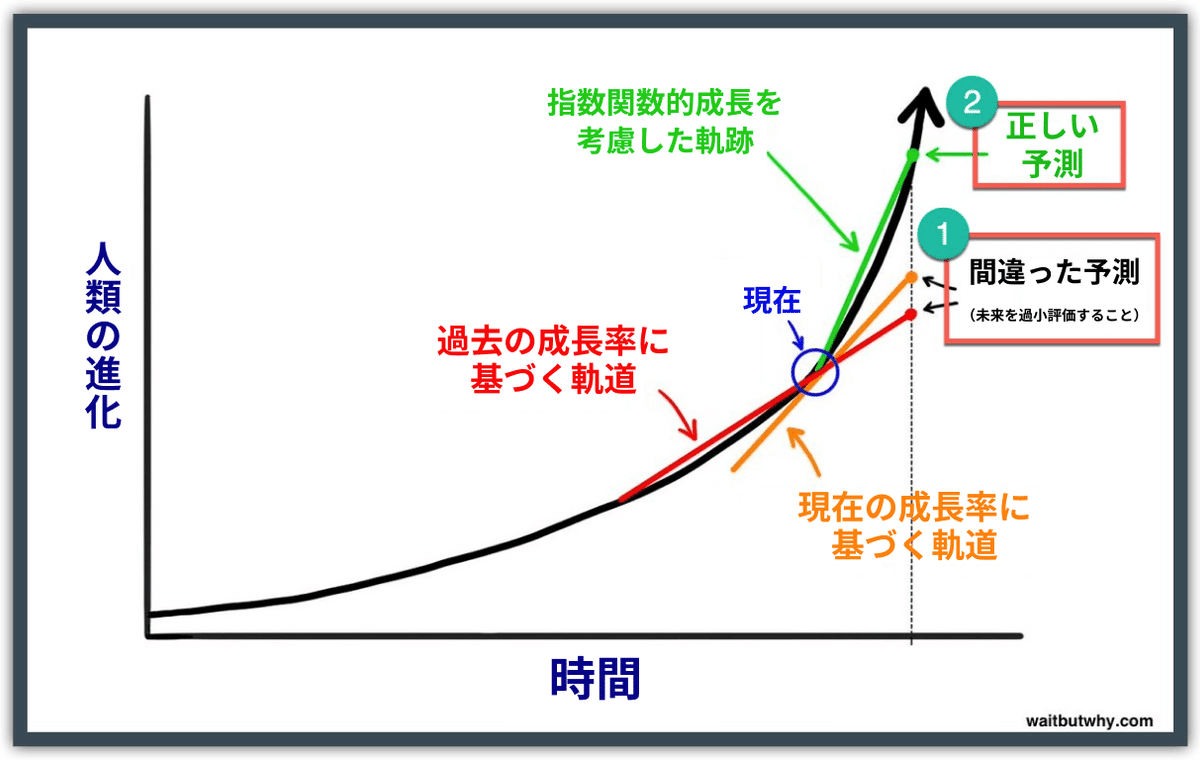

1) 歴史に関しては、私たちは直線的に考えがちです。今後30年の進歩を想像するとき、私たちは過去30年の進歩を指標として、どれくらいのことが起こりそうかを見ています。21世紀にどの程度世界が変化するかを考えるとき、私たちは単に20世紀の進歩を2000年に加えるだけです。これは、1750年の人が1500年の人を連れてきて、同じ距離を先に進んだときに自分の頭が吹っ飛ぶのと同じくらい相手の頭を吹っ飛ばすことを期待したときと同じ間違いです。私たちにとって最も直感的なのは、指数関数的に考えるべきところを、直線的に考えることです。もし誰かがもっと賢明であれば、過去30年を見るのではなく、現在の進歩率を基に判断して、今後30年の進歩を予測するかもしれません。それはより正確でしょうが、それでもかなり間違っているでしょう。未来について正しく考えるためには、物事が現在のペースよりもずっと速いペースで動いていると想像する必要があります。

1) When it comes to history, we think in straight lines. When we imagine the progress of the next 30 years, we look back to the progress of the previous 30 as an indicator of how much will likely happen. When we think about the extent to which the world will change in the 21st century, we just take the 20th century progress and add it to the year 2000. This was the same mistake our 1750 guy made when he got someone from 1500 and expected to blow his mind as much as his own was blown going the same distance ahead. It’s most intuitive for us to think linearly, when we should be thinking exponentially. If someone is being more clever about it, they might predict the advances of the next 30 years not by looking at the previous 30 years, but by taking the current rate of progress and judging based on that. They’d be more accurate, but still way off. In order to think about the future correctly, you need to imagine things moving at a much faster rate than they’re moving now.

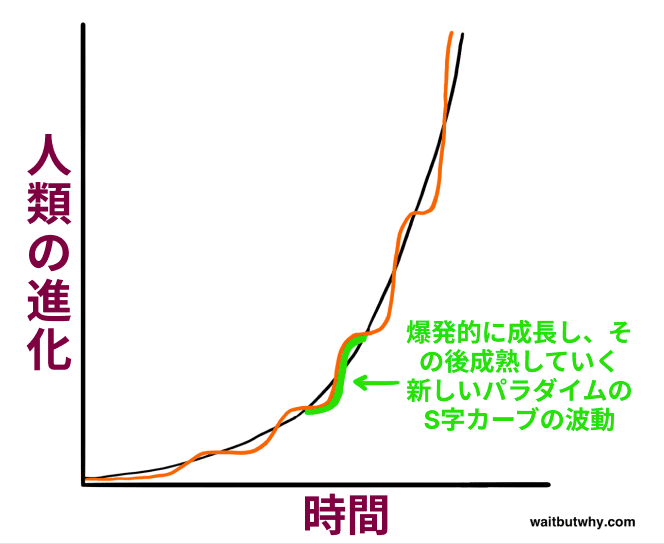

2)ごく最近の歴史の軌跡は、しばしば歪んだ物語を語ります。まず、急な指数関数曲線でも、ほんの一部分しか見ていないと、直線的に見えます。巨大な円の一部分を近くで見ると、ほとんど直線のように見えるのと同じです。次に、指数関数的な成長は完全にスムーズで一様ではありません。カーツワイルは、進歩は「S字カーブ」で起こると説明しています。

2) The trajectory of very recent history often tells a distorted story. First, even a steep exponential curve seems linear when you only look at a tiny slice of it, the same way if you look at a little segment of a huge circle up close, it looks almost like a straight line. Second, exponential growth isn’t totally smooth and uniform. Kurzweil explains that progress happens in “S-curves”:

Sは、新しいパラダイムが世界を席巻したときの進歩の波によって作られます。このカーブは3つの段階を経ます。

1. 緩やかな成長(指数関数的成長の初期段階

2. 急速な成長(指数関数的成長の後期の爆発的な段階

3. 特定のパラダイムが成熟するにつれての水平化

An S is created by the wave of progress when a new paradigm sweeps the world. The curve goes through three phases:

1. Slow growth (the early phase of exponential growth)

2. Rapid growth (the late, explosive phase of exponential growth)

3. A leveling off as the particular paradigm matures

ごく最近の歴史だけを見ていると、現在のS字カーブのどの部分にいるかによって、物事がどれだけ速く進歩しているかの認識が曖昧になってしまうことがあります。1995年から2007年までの時期は、インターネットの爆発的普及、マイクロソフト、グーグル、フェイスブックの一般への浸透、ソーシャルネットワーキングの誕生、携帯電話やスマートフォンの登場などがありました。これがフェーズ2、つまりSの成長期です。しかし、2008年から2015年は、少なくとも技術面ではそれほど画期的ではありませんでした。今日、未来について考えている人は、現在の進歩率を測るために過去数年を調べるかもしれませんが、それではもっと大きな全体像を見失ってしまいます。実際、新しい巨大なフェーズ2の成長期が今にも始まろうとしているのかもしれません。

If you look only at very recent history, the part of the S-curve you’re on at the moment can obscure your perception of how fast things are advancing. The chunk of time between 1995 and 2007 saw the explosion of the internet, the introduction of Microsoft, Google, and Facebook into the public consciousness, the birth of social networking, and the introduction of cell phones and then smart phones. That was Phase 2: the growth spurt part of the S. But 2008 to 2015 has been less groundbreaking, at least on the technological front. Someone thinking about the future today might examine the last few years to gauge the current rate of advancement, but that’s missing the bigger picture. In fact, a new, huge Phase 2 growth spurt might be brewing right now.

3) 自分自身の経験が、未来についての頑固なオヤジにさせてしまいます。私たちは自分の経験を基に世界についての考えを持っていますが、その経験が「物事の進み方」として最近の過去の成長率を頭に叩き込んでいるのです。また、私たちの想像力には限界があり、経験を基に未来を予測しようとしますが、しばしば私たちの知識だけでは未来を正確に考えるための道具にはならないのです。2 私たちが物事の仕組みについての経験に基づいた考え方と矛盾する未来の予測を聞くと、その予測は naive でなければならないという本能が働きます。もし私がこの記事の後半で、あなたは150歳、250歳まで生きるかもしれない、あるいはまったく死なないかもしれないと言ったら、あなたの本能は「それは馬鹿げている。歴史から分かることが一つあるとすれば、誰もが死ぬということだ」と言うでしょう。そして、確かに過去には死ななかった人はいませんでした。しかし、飛行機が発明される前に飛行機に乗った人もいなかったのです。

3) Our own experience makes us stubborn old men about the future. We base our ideas about the world on our personal experience, and that experience has ingrained the rate of growth of the recent past in our heads as “the way things happen.” We’re also limited by our imagination, which takes our experience and uses it to conjure future predictions—but often, what we know simply doesn’t give us the tools to think accurately about the future.2 When we hear a prediction about the future that contradicts our experience-based notion of how things work, our instinct is that the prediction must be naive. If I tell you, later in this post, that you may live to be 150, or 250, or not die at all, your instinct will be, “That’s stupid—if there’s one thing I know from history, it’s that everybody dies.” And yes, no one in the past has not died. But no one flew airplanes before airplanes were invented either.

ですから、この投稿を読んでいて 「 ん~」 と感じるのは正しいように感じるかもしれませんが、実際にはおそらく間違っているのです。事実、本当に論理的に考えて、歴史的なパターンが続くことを期待するならば、直感的に期待するよりもはるかに多くのことが今後数十年で変化するはずだと結論づけるべきです。また、ある惑星で最も進化した種が、どんどん大きな飛躍を加速度的に続けていけば、やがて、人間であることの意味についての認識を完全に変えてしまうほどの大きな飛躍をすることになるはずです。まるで、進化が知性に向かって大きな飛躍を続け、ついには人間へと飛躍したことで、地球上のあらゆる生物の生き方を完全に変えてしまったようなものです。そして、今日の科学技術で何が起こっているのかについて少し時間をかけて読んでみると、現在私たちが知っている生活が次に来る飛躍に耐えられないことを静かに示唆する多くの兆候が見えてきます。

So while nahhhhh might feel right as you read this post, it’s probably actually wrong. The fact is, if we’re being truly logical and expecting historical patterns to continue, we should conclude that much, much, much more should change in the coming decades than we intuitively expect. Logic also suggests that if the most advanced species on a planet keeps making larger and larger leaps forward at an ever-faster rate, at some point, they’ll make a leap so great that it completely alters life as they know it and the perception they have of what it means to be a human—kind of like how evolution kept making great leaps toward intelligence until finally it made such a large leap to the human being that it completely altered what it meant for any creature to live on planet Earth. And if you spend some time reading about what’s going on today in science and technology, you start to see a lot of signs quietly hinting that life as we currently know it cannot withstand the leap that’s coming next.

超知能への道

AIとは何か?

私と同じように、あなたも以前は人工知能を馬鹿げたSF的な概念だと思っていたかもしれませんが、最近では真面目な人たちがそれについて語っているのを耳にするようになり、よく分からなくなってきているのではないでしょうか。

多くの人が人工知能という言葉に混乱する理由は3つあります。

If you’re like me, you used to think Artificial Intelligence was a silly sci-fi concept, but lately you’ve been hearing it mentioned by serious people, and you don’t really quite get it.

There are three reasons a lot of people are confused about the term AI:

1)人工知能を映画と結び付けてイメージするから。スター・ウォーズ、ターミネーター、2001年宇宙の旅、ジェットソンズでさえそうです。それらはフィクションであり、登場するロボットのキャラクターもフィクションです。だから、人工知能を少し架空のものに聞こえさせてしまうのです。

2)人工知能は幅広いトピックだから。電卓から自動運転車、さらには将来世界を大きく変える可能性のあるものまで、さまざまなものを指します。人工知能がこれらすべてを指すので混乱するのです。

3)日常生活で人工知能を頻繁に使っているのに、それが人工知能だと気づかないことが多いから。1956年に「人工知能」という言葉を作ったジョン・マッカーシーは、「うまく機能し始めると、誰もそれを人工知能とは呼ばなくなる」と嘆いていました。このような現象のため、人工知能は現実というよりも神話的な未来予測のように聞こえることが多いのです。同時に、過去のポップな概念で実を結ばなかったようにも聞こえます。レイ・カーツワイルは、人工知能が1980年代に衰退したと言う人の声を聞くと、「2000年代初頭のドットコムバブル崩壊でインターネットが死んだと主張するようなもの」だと話しています。

1) We associate AI with movies. Star Wars. Terminator. 2001: A Space Odyssey. Even the Jetsons. And those are fiction, as are the robot characters. So it makes AI sound a little fictional to us.

2) AI is a broad topic. It ranges from your phone’s calculator to self-driving cars to something in the future that might change the world dramatically. AI refers to all of these things, which is confusing.

3) We use AI all the time in our daily lives, but we often don’t realize it’s AI. John McCarthy, who coined the term “Artificial Intelligence” in 1956, complained that “as soon as it works, no one calls it AI anymore.”4 Because of this phenomenon, AI often sounds like a mythical future prediction more than a reality. At the same time, it makes it sound like a pop concept from the past that never came to fruition. Ray Kurzweil says he hears people say that AI withered in the 1980s, which he compares to “insisting that the Internet died in the dot-com bust of the early 2000s.”

そこで、混乱を解きましょう。まず、ロボットのことは忘れてください。ロボットは人工知能の入れ物で、人間の形を模倣していることもあれば、そうでないこともあります。しかし、人工知能そのものはロボットの中のコンピュータなのです。人工知能は脳であり、ロボットは体です。体を持っていなくてもいいのです。例えば、Siriの背後にあるソフトウェアとデータは人工知能であり、私たちが聞く女性の声はその人工知能の擬人化であり、ロボットは全く関係ありません。

So let’s clear things up. First, stop thinking of robots. A robot is a container for AI, sometimes mimicking the human form, sometimes not—but the AI itself is the computer inside the robot. AI is the brain, and the robot is its body—if it even has a body. For example, the software and data behind Siri is AI, the woman’s voice we hear is a personification of that AI, and there’s no robot involved at all.

次に、「シンギュラリティ」や「技術的特異点」という言葉を聞いたことがあるかもしれません。この言葉は、数学で漸近線のような通常のルールが適用されない状況を表すのに使われてきました。物理学では、無限に小さく高密度のブラックホールや、ビッグバン直前に私たち全てが押し込められていた点のような、やはり通常のルールが適用されない現象を表すのに使われてきました。1993年、ヴァーナー・ヴィンジは有名なエッセイの中で、私たちの技術の知性が人間の知性を超える未来のある時点に、この言葉を適用しました。彼にとってそれは、私たちの知っている生命が永遠に変わり、通常のルールが適用されなくなる瞬間でした。その後、レイ・カーツワイルは「加速する変化の法則」が非常に極端なペースに達し、技術の進歩が一見無限のペースで起こるようになり、その後私たちが全く新しい世界に生きることになる時期としてシンギュラリティを定義し、少し話を混乱させました。私は、今日の人工知能研究者の多くがこの言葉の使用をやめており、混乱を招くので、ここではあまり使わないことにします(この考えには焦点を当て続けますが)。

Secondly, you’ve probably heard the term “singularity” or “technological singularity.” This term has been used in math to describe an asymptote-like situation where normal rules no longer apply. It’s been used in physics to describe a phenomenon like an infinitely small, dense black hole or the point we were all squished into right before the Big Bang. Again, situations where the usual rules don’t apply. In 1993, Vernor Vinge wrote a famous essay in which he applied the term to the moment in the future when our technology’s intelligence exceeds our own—a moment for him when life as we know it will be forever changed and normal rules will no longer apply. Ray Kurzweil then muddled things a bit by defining the singularity as the time when the Law of Accelerating Returns has reached such an extreme pace that technological progress is happening at a seemingly-infinite pace, and after which we’ll be living in a whole new world. I found that many of today’s AI thinkers have stopped using the term, and it’s confusing anyway, so I won’t use it much here (even though we’ll be focusing on that idea throughout).

最後に、人工知能は幅広い概念なので、多くの異なるタイプや形態の人工知能がありますが、私たちが考える必要がある重要なカテゴリは、人工知能の能力に基づいています。大きく分けて3つの人工知能能力カテゴリがあります。

Finally, while there are many different types or forms of AI since AI is a broad concept, the critical categories we need to think about are based on an AI’s caliber. There are three major AI caliber categories:

人工知能能力1)特化型人工知能(ANI):弱いAIとも呼ばれる狭い人工知能は、ある特定の分野に特化した人工知能です。チェスの世界チャンピオンに勝つことができる人工知能がありますが、それができるのはそれだけです。ハードディスクにデータをより良い方法で保存する方法を考え出すように頼んでも、きょとんとするでしょう。

人工知能能力2)汎用人工知能(AGI):ストロング人工知能、あるいは人間レベルの人工知能とも呼ばれる汎用人工知能は、全ての面で人間と同じくらい賢いコンピュータのことを指します。人間ができる知的作業は何でもこなせるマシンです。AGIを作ることは、ANIを作ることよりもはるかに難しい課題で、まだ実現されていません。リンダ・ゴットフレッドソン教授は、知能を「とりわけ推論、計画、問題解決、抽象的思考、複雑な考えの理解、素早い学習、経験からの学習を含む、非常に一般的な精神的能力」と表現しています。AGIはそれらすべてをあなたと同じくらい簡単にこなせるでしょう。

人工知能能力3)超人工知能(ASI):オックスフォードの哲学者で人工知能の第一人者ニック・ボストロムは、超知能を「科学的創造性、一般的な知恵、社交スキルを含む実質的にすべての分野で、最高の人間の頭脳よりもはるかに賢い知性」と定義しています。超人工知能は、人間よりほんの少し賢いコンピュータから、全ての面で人間の何兆倍も賢いコンピュータまでを指します。超人工知能こそが、人工知能というトピックがこれほどホットな話題である理由であり、「不死」と「絶滅」という言葉がこれらの記事に何度も登場する理由なのです。

AI Caliber 1) Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI): Sometimes referred to as Weak AI, Artificial Narrow Intelligence is AI that specializes in one area. There’s AI that can beat the world chess champion in chess, but that’s the only thing it does. Ask it to figure out a better way to store data on a hard drive, and it’ll look at you blankly.

AI Caliber 2) Artificial General Intelligence (AGI): Sometimes referred to as Strong AI, or Human-Level AI, Artificial General Intelligence refers to a computer that is as smart as a human across the board—a machine that can perform any intellectual task that a human being can. Creating AGI is a much harder task than creating ANI, and we’re yet to do it. Professor Linda Gottfredson describes intelligence as “a very general mental capability that, among other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly, and learn from experience.” AGI would be able to do all of those things as easily as you can.

AI Caliber 3) Artificial Superintelligence (ASI): Oxford philosopher and leading AI thinker Nick Bostrom defines superintelligence as “an intellect that is much smarter than the best human brains in practically every field, including scientific creativity, general wisdom and social skills.” Artificial Superintelligence ranges from a computer that’s just a little smarter than a human to one that’s trillions of times smarter—across the board. ASI is the reason the topic of AI is such a spicy meatball and why the words “immortality” and “extinction” will both appear in these posts multiple times.

現時点で、人類は最も低い能力の人工知能、つまり狭い人工知能を多くの方法で制覇しており、それはどこにでもあります。人工知能革命とは、狭い人工知能から汎用人工知能を経て超人工知能に至る道のりのことであり、私たちがそれを生き延びるかどうかはわかりませんが、いずれにせよすべてが変わるでしょう。

この分野の第一人者たちが考えるこの道のりがどのようなものか、そしてこの革命が思っているよりもずっと早く起こるかもしれない理由を、詳しく見ていきましょう。

As of now, humans have conquered the lowest caliber of AI—ANI—in many ways, and it’s everywhere. The AI Revolution is the road from ANI, through AGI, to ASI—a road we may or may not survive but that, either way, will change everything.

Let’s take a close look at what the leading thinkers in the field believe this road looks like and why this revolution might happen way sooner than you might think:

現在の世界 - ANIが動かす世界

人工狭域知能(ANI)とは、特定のタスクにおいて人間の知能や効率と同等かそれ以上の性能を持つ機械知能のことです。いくつか例を挙げてみましょう。

車には多くのANIシステムが搭載されています。アンチロックブレーキを制御するコンピューターから、燃料噴射システムのパラメーターを調整するコンピューターまで多岐にわたります。現在テスト中のGoogleの自動運転車には、周囲の環境を認識し反応する高度なANIシステムが搭載されています。

Cars are full of ANI systems, from the computer that figures out when the anti-lock brakes should kick in to the computer that tunes the parameters of the fuel injection systems. Google’s self-driving car, which is being tested now, will contain robust ANI systems that allow it to perceive and react to the world around it.

スマートフォンは小さなANI工場です。地図アプリでナビゲーションしたり、Pandoraでパーソナライズされた音楽のおすすめを受けたり、明日の天気を確認したり、Siriと話したりと、日常のあらゆる場面でANIを使っています。

Your phone is a little ANI factory. When you navigate using your map app, receive tailored music recommendations from Pandora, check tomorrow’s weather, talk to Siri, or dozens of other everyday activities, you’re using ANI.

メールのスパムフィルターは典型的なANIの一種です。スパムかどうかを判断する知性を初期状態で持っており、ユーザーの好みに合わせて学習し、知性を適応させていきます。Nest Thermostatも同様に、ユーザーの典型的な生活パターンを学習し、それに応じて動作します。

Your email spam filter is a classic type of ANI—it starts off loaded with intelligence about how to figure out what’s spam and what’s not, and then it learns and tailors its intelligence to you as it gets experience with your particular preferences. The Nest Thermostat does the same thing as it starts to figure out your typical routine and act accordingly.

Amazonで商品を検索した後、別のサイトでその商品が「おすすめ商品」として表示されたり、Facebookが友達候補を不思議と的確に提案してきたりする際の不気味さを感じたことはありませんか?これは複数のANIシステムが連携し、ユーザーの情報や好みを共有し、それをもとに表示内容を決定しているのです。Amazonの「この商品を買った人はこんな商品も買っています」も同様で、何百万人ものユーザーの行動から情報を収集し、巧みにアップセルしてより多くの商品を購入してもらうためのANIシステムです。

You know the whole creepy thing that goes on when you search for a product on Amazon and then you see that as a “recommended for you” product on a different site, or when Facebook somehow knows who it makes sense for you to add as a friend? That’s a network of ANI systems, working together to inform each other about who you are and what you like and then using that information to decide what to show you. Same goes for Amazon’s “People who bought this also bought…” thing—that’s an ANI system whose job it is to gather info from the behavior of millions of customers and synthesize that info to cleverly upsell you so you’ll buy more things.

Google翻訳は、もう一つの代表的なANIシステムで、狭い範囲のタスクで驚くほどの性能を発揮します。音声認識もそうですが、この2つのANIをタッグを組ませたアプリもあり、ある言語で話した文章を別の言語で喋り返してくれます。

Google Translate is another classic ANI system—impressively good at one narrow task. Voice recognition is another, and there are a bunch of apps that use those two ANIs as a tag team, allowing you to speak a sentence in one language and have the phone spit out the same sentence in another.

飛行機が着陸する際、どのゲートに行くかを決めるのは人間ではありません。チケットの価格を決めるのも同様です。

When your plane lands, it’s not a human that decides which gate it should go to. Just like it’s not a human that determined the price of your ticket.

チェッカー、チェス、スクラブル、バックギャモン、オセロの世界チャンピオンは、すべてANIシステムです。

The world’s best Checkers, Chess, Scrabble, Backgammon, and Othello players are now all ANI systems.

Googleの検索は、ページのランク付けやユーザーに合わせた検索結果の表示など、非常に洗練された手法を持つ大規模なANI脳です。Facebookのニュースフィードも同様です。

Google search is one large ANI brain with incredibly sophisticated methods for ranking pages and figuring out what to show you in particular. Same goes for Facebook’s Newsfeed.

これらは消費者向けの世界の一部に過ぎません。軍事、製造、金融(米国市場で取引される株式の半分以上がアルゴリズムを用いたAIによる高頻度取引6)などの分野や業界でも、高度なANIシステムが広く使われています。また、医師の診断を支援するエキスパートシステムや、最も有名なものとしては、事実を大量に蓄え、巧みなトレベック風の言い回しを理解し、「ジェパディ!」の歴代チャンピオンを圧倒的に破ったIBMのワトソンなどがあります。

And those are just in the consumer world. Sophisticated ANI systems are widely used in sectors and industries like military, manufacturing, and finance (algorithmic high-frequency AI traders account for more than half of equity shares traded on US markets6), and in expert systems like those that help doctors make diagnoses and, most famously, IBM’s Watson, who contained enough facts and understood coy Trebek-speak well enough to soundly beat the most prolific Jeopardy champions.

現状のANIシステムは、それほど怖いものではありません。最悪の場合、不具合のあるANIや badly-programmed なANIが、送電網の停止、原子力発電所の有害な誤作動、金融市場の災害(2010年のフラッシュ・クラッシュのように、ANIプログラムが予期せぬ状況に誤った反応をし、一時的に株式市場が暴落、1兆ドルの市場価値が失われ、ミスが修正された後も一部しか回復しなかった)などの孤立した大惨事を引き起こす可能性があります。

ANI systems as they are now aren’t especially scary. At worst, a glitchy or badly-programmed ANI can cause an isolated catastrophe like knocking out a power grid, causing a harmful nuclear power plant malfunction, or triggering a financial markets disaster (like the 2010 Flash Crash when an ANI program reacted the wrong way to an unexpected situation and caused the stock market to briefly plummet, taking $1 trillion of market value with it, only part of which was recovered when the mistake was corrected).

しかし、ANIは存在的脅威を引き起こす能力はないものの、比較的無害なANIのこの大規模で複雑なエコシステムを、近い将来やってくる世界を一変させるハリケーンの前兆と捉えるべきです。新しいANIの革新は、ひっそりとAGIやASIへの道のりにレンガを積み重ねているのです。あるいは、Aaron Saenzが述べているように、私たちの世界のANIシステムは「原始地球の原始スープのアミノ酸のようなもの」、つまり、ある予期せぬ日に目覚めた生命の無生物的な素材なのです。

But while ANI doesn’t have the capability to cause an existential threat, we should see this increasingly large and complex ecosystem of relatively-harmless ANI as a precursor of the world-altering hurricane that’s on the way. Each new ANI innovation quietly adds another brick onto the road to AGI and ASI. Or as Aaron Saenz sees it, our world’s ANI systems “are like the amino acids in the early Earth’s primordial ooze”—the inanimate stuff of life that, one unexpected day, woke up.

ANIからAGIへの道のり

なぜそれがとても難しいのか

人間の知性がどれほど素晴らしいものかを理解するには、人間と同じくらい賢いコンピューターを作ることがどれほど信じられないほど難しいことかを学ぶのが一番です。超高層ビルを建てたり、人間を宇宙に送り込んだり、ビッグバンがどのように起こったのかを詳しく解明したりするのは、私たち自身の脳を理解したり、それと同じくらいクールなものを作ったりするよりもはるかに簡単なのです。現時点では、人間の脳は既知の宇宙で最も複雑な物体です。

Nothing will make you appreciate human intelligence like learning about how unbelievably challenging it is to try to create a computer as smart as we are. Building skyscrapers, putting humans in space, figuring out the details of how the Big Bang went down—all far easier than understanding our own brain or how to make something as cool as it. As of now, the human brain is the most complex object in the known universe.

興味深いのは、AGI(一般的な意味で人間と同じくらい賢いコンピューター、特定の分野だけでなく)を構築しようとする際の難しい部分は、直感的に考えるものではないということです。2つの10桁の数字を一瞬で掛け算できるコンピューターを作るのは信じられないほど簡単です。犬を見て、それが犬なのか猫なのかを答えられるコンピューターを作るのは途方もなく難しいのです。どんな人間よりもチェスに強いAIを作る?それは達成されています。6歳児の絵本の一節を読んで、単語を認識するだけでなく、その意味を理解できるAIを作る?Googleは現在、何十億ドルもの費用をかけてそれを実現しようとしています。微積分、金融市場戦略、言語翻訳などの難しいことは、コンピューターにとっては気が遠くなるほど簡単ですが、視覚、動作、運動、知覚などの簡単なことは、コンピューターにとっては信じられないほど難しいのです。あるいは、コンピューター科学者のDonald Knuthが言うように、「AIは今や『考える』ことを必要とするほとんどすべてのことに成功してきたが、人間や動物が『考えずに』行うほとんどのことを行うことには失敗してきた」のです。

What’s interesting is that the hard parts of trying to build AGI (a computer as smart as humans in general, not just at one narrow specialty) are not intuitively what you’d think they are. Build a computer that can multiply two ten-digit numbers in a split second—incredibly easy. Build one that can look at a dog and answer whether it’s a dog or a cat—spectacularly difficult. Make AI that can beat any human in chess? Done. Make one that can read a paragraph from a six-year-old’s picture book and not just recognize the words but understand the meaning of them? Google is currently spending billions of dollars trying to do it. Hard things—like calculus, financial market strategy, and language translation—are mind-numbingly easy for a computer, while easy things—like vision, motion, movement, and perception—are insanely hard for it. Or, as computer scientist Donald Knuth puts it, “AI has by now succeeded in doing essentially everything that requires ‘thinking’ but has failed to do most of what people and animals do ‘without thinking.'”7

これについて考えてみると、私たちにとって簡単そうに見えることは実は信じられないほど複雑であり、それらのスキルが何億年もの動物の進化によって私たち(そしてほとんどの動物)に最適化されているために簡単に見えるだけだということがすぐにわかります。物に向かって手を伸ばすとき、目と連動して、肩、肘、手首の筋肉、腱、骨が一瞬にして一連の物理演算を行い、3次元の空間で手をまっすぐに動かすことができるのです。それは脳内にその完璧なソフトウェアを持っているから、あなたにとっては容易に感じられるのです。新しいアカウントを登録する際に、マルウェアが傾いた文字の認識テストを理解できないのは、マルウェアが愚かだからではなく、あなたの脳がそれを可能にできるほど優れているからだというのも同じ考え方です。

What you quickly realize when you think about this is that those things that seem easy to us are actually unbelievably complicated, and they only seem easy because those skills have been optimized in us (and most animals) by hundreds of millions of years of animal evolution. When you reach your hand up toward an object, the muscles, tendons, and bones in your shoulder, elbow, and wrist instantly perform a long series of physics operations, in conjunction with your eyes, to allow you to move your hand in a straight line through three dimensions. It seems effortless to you because you have perfected software in your brain for doing it. Same idea goes for why it’s not that malware is dumb for not being able to figure out the slanty word recognition test when you sign up for a new account on a site—it’s that your brain is super impressive for being able to.

一方で、大きな数字の掛け算やチェスは生物にとって新しい活動であり、それらに精通するための時間が全くなかったため、コンピューターはそれほど頑張らなくても人間に勝てるのです。考えてみてください。大きな数字を掛け算できるプログラムを作るのと、Bの本質を理解して、何千もの予測不可能なフォントや手書きでBを示されても、それがBだとすぐにわかるプログラムを作るのと、どちらがいいですか?

On the other hand, multiplying big numbers or playing chess are new activities for biological creatures and we haven’t had any time to evolve a proficiency at them, so a computer doesn’t need to work too hard to beat us. Think about it—which would you rather do, build a program that could multiply big numbers or one that could understand the essence of a B well enough that you could show it a B in any one of thousands of unpredictable fonts or handwriting and it could instantly know it was a B?

楽しい例を1つ挙げましょう。これを見ると、あなたもコンピューターも、2つの異なる色合いが交互に現れる長方形だということがわかります。

One fun example—when you look at this, you and a computer both can figure out that it’s a rectangle with two distinct shades, alternating:

ここまでは引き分けです。しかし、黒を拾って全体像を明らかにすると...

Tied so far. But if you pick up the black and reveal the whole image…

...あなたは様々な不透明や半透明のシリンダー、格子、3次元の角などを問題なく説明できますが、コンピューターは見事に失敗するでしょう。コンピューターは見えるもの、つまり実際にそこにあるものである様々な2次元の形とそのいくつかの異なる色合いを説明するでしょう。あなたの脳は、その画像が表現しようとしている奥行き、色の混合、部屋の照明を解釈するために、たくさんの素晴らしいことをしているのです。そして下の画像を見ると、コンピューターは2次元の白、黒、グレーのコラージュを見ますが、あなたはそれが本当は何であるか、完全に黒い3次元の岩の写真であることを簡単に見抜くことができます。

…you have no problem giving a full description of the various opaque and translucent cylinders, slats, and 3-D corners, but the computer would fail miserably. It would describe what it sees—a variety of two-dimensional shapes in several different shades—which is actually what’s there. Your brain is doing a ton of fancy shit to interpret the implied depth, shade-mixing, and room lighting the picture is trying to portray.8 And looking at the picture below, a computer sees a two-dimensional white, black, and gray collage, while you easily see what it really is—a photo of an entirely-black, 3-D rock:

そして、私たちが今まで述べてきたことはすべて、まだ停滞した情報を取り入れて処理することだけです。人間レベルの知性を持つためには、コンピューターは微妙な表情の違い、喜び、安堵、満足、満足感、喜びの区別、そして『ブレイブハート』が素晴らしかったのに『パトリオット』がひどかった理由などを理解しなければなりません。

気の遠くなるような話です。

では、どうすればそこにたどり着けるのでしょうか。

And everything we just mentioned is still only taking in stagnant information and processing it. To be human-level intelligent, a computer would have to understand things like the difference between subtle facial expressions, the distinction between being pleased, relieved, content, satisfied, and glad, and why Braveheart was great but The Patriot was terrible.

Daunting.

So how do we get there?

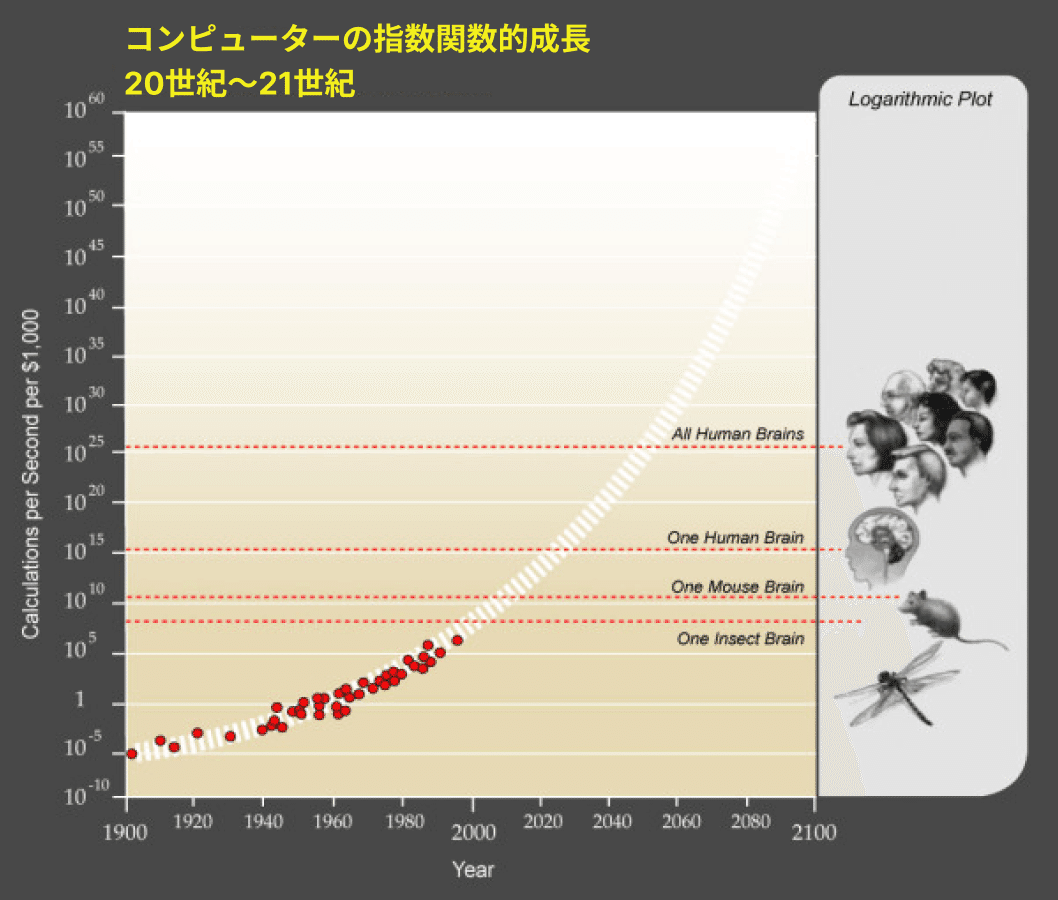

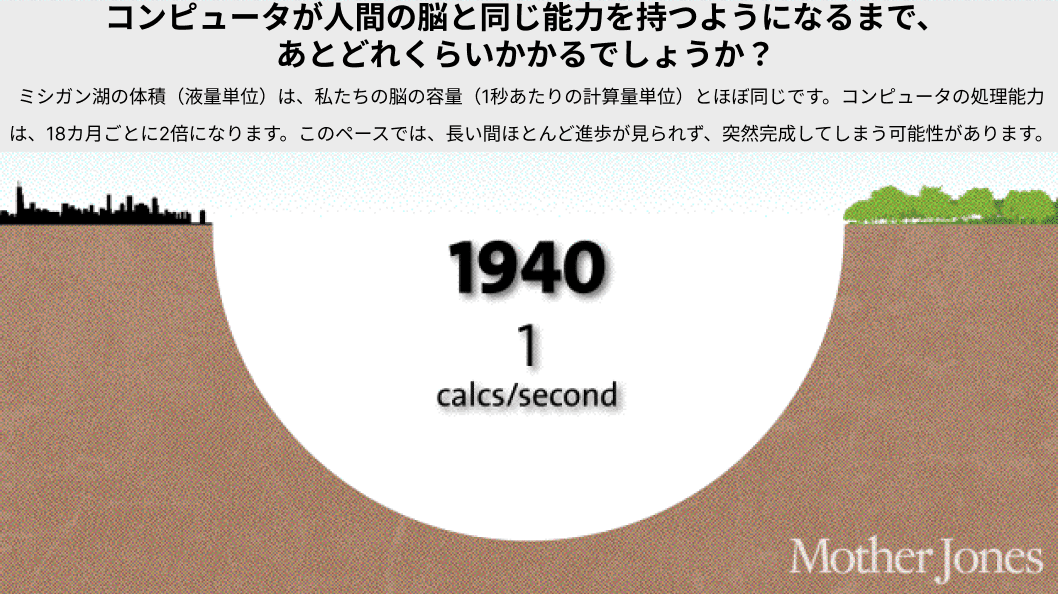

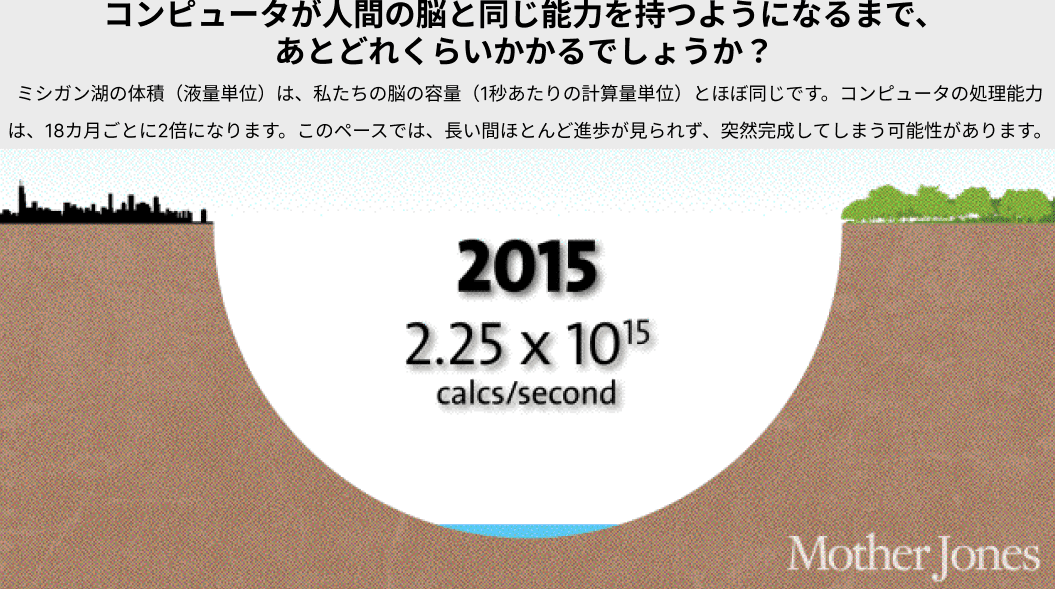

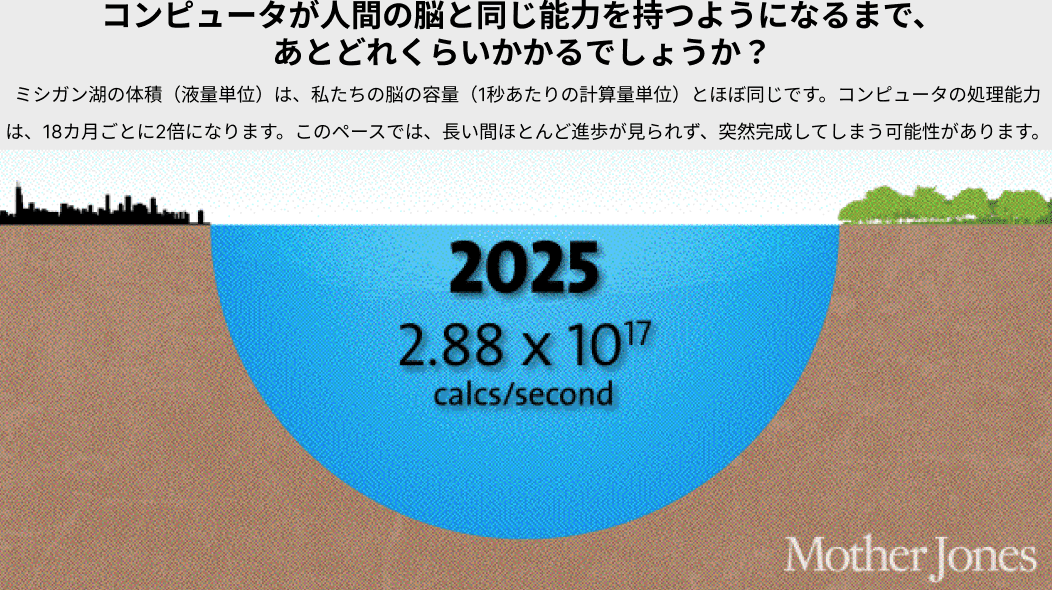

AGIを生み出す第一の鍵:計算能力の向上

AGIを実現可能にするには、コンピュータハードウェアの性能向上が不可欠です。AIシステムが人間の脳と同等の知性を持つためには、脳の生の計算能力に匹敵する必要があるでしょう。

One thing that definitely needs to happen for AGI to be a possibility is an increase in the power of computer hardware. If an AI system is going to be as intelligent as the brain, it’ll need to equal the brain’s raw computing capacity.

この能力を表す一つの方法は、脳が管理できる毎秒の総計算量(cps)で、脳内の各構造の最大cpsを算出し、それらを全て足し合わせることで導き出せます。

One way to express this capacity is in the total calculations per second (cps) the brain could manage, and you could come to this number by figuring out the maximum cps of each structure in the brain and then adding them all together.

レイ・カーツワイルは、ある構造のcpsの専門家による推定値と、その構造の重量が脳全体に占める割合を用いて、比例計算により総計を推定するという近道を考案しました。少し怪しげですが、彼は様々な専門家による異なる領域の推定値を用いて何度もこれを行い、総計は常に同じ範囲、約1016、つまり10京cpsに到達しました。

Ray Kurzweil came up with a shortcut by taking someone’s professional estimate for the cps of one structure and that structure’s weight compared to that of the whole brain and then multiplying proportionally to get an estimate for the total. Sounds a little iffy, but he did this a bunch of times with various professional estimates of different regions, and the total always arrived in the same ballpark—around 1016, or 10 quadrillion cps.

現在、世界最速のスーパーコンピュータである中国の天河二号は、実際にこの数値を上回る約34京cpsを記録しています。しかし、天河二号は720平方メートルの空間を占有し、24メガワットの電力を消費し(脳はわずか20ワットで動作)、建設に3億9000万ドルを要するなど、非常に扱いにくいものでもあります。まだ幅広い用途や、商業的・産業的用途にも特に適用できるものではありません。

Currently, the world’s fastest supercomputer, China’s Tianhe-2, has actually beaten that number, clocking in at about 34 quadrillion cps. But Tianhe-2 is also a dick, taking up 720 square meters of space, using 24 megawatts of power (the brain runs on just 20 watts), and costing $390 million to build. Not especially applicable to wide usage, or even most commercial or industrial usage yet.

カーツワイルは、1,000ドルで購入できるcpsの数を見ることで、コンピュータの状態を考えるべきだと提案しています。その数値が人間レベルの10京cpsに到達すれば、AGIが生活の非常に現実的な一部になる可能性があるということです。

Kurzweil suggests that we think about the state of computers by looking at how many cps you can buy for $1,000. When that number reaches human-level—10 quadrillion cps—then that’ll mean AGI could become a very real part of life.

ムーアの法則は、世界の最大計算能力がおよそ2年ごとに倍増するという、歴史的に信頼できる法則です。つまり、コンピュータのハードウェアの進歩は、歴史を通じた人類の一般的な進歩と同様に指数関数的に成長するのです。これがカーツワイルのcps/1,000ドルの指標とどのように関連するかを見ると、現在は約10兆cps/1,000ドルで、このグラフの予測軌道とちょうど一致しています。

Moore’s Law is a historically-reliable rule that the world’s maximum computing power doubles approximately every two years, meaning computer hardware advancement, like general human advancement through history, grows exponentially. Looking at how this relates to Kurzweil’s cps/$1,000 metric, we’re currently at about 10 trillion cps/$1,000, right on pace with this graph’s predicted trajectory:9

2015年現在、1,000ドルのコンピュータはマウスの脳を上回る性能を持ち、人間のレベルの千分の一程度に達しています。これは一見大したことないように思えるかもしれません。しかし、1985年には人間レベルの一兆分の一、1995年には一億分の一、2005年には百万分の一だったことを思い出してください。2015年に千分の一のレベルに達したということは、2025年までには手頃な価格で脳の能力に匹敵するコンピュータが登場するペースであることを意味しています。

So the world’s $1,000 computers are now beating the mouse brain and they’re at about a thousandth of human level. This doesn’t sound like much until you remember that we were at about a trillionth of human level in 1985, a billionth in 1995, and a millionth in 2005. Being at a thousandth in 2015 puts us right on pace to get to an affordable computer by 2025 that rivals the power of the brain.

ハードウェア面では、AGIに必要な生の処理能力は現在、中国ですでに技術的に利用可能であり、10年以内には手頃な価格で広く普及するAGIレベルのハードウェアが準備できるでしょう。しかし、生の計算能力だけでは、コンピュータに汎用的な知性をもたらすことはできません。次の問題は、そのすべての能力にどのようにして人間レベルの知性をもたらすかということです。

So on the hardware side, the raw power needed for AGI is technically available now, in China, and we’ll be ready for affordable, widespread AGI-caliber hardware within 10 years. But raw computational power alone doesn’t make a computer generally intelligent—the next question is, how do we bring human-level intelligence to all that power?

第2の鍵: AGIを賢くする方法

脳を盗作する これは、隣の席に座っている頭の良い子がなぜあんなにテストの成績が良いのかを科学者が苦労して解明しようとするようなものです。一生懸命勉強しても、その子には到底及ばない。そして最後には「もういい、その子の答案を写させてもらおう」と決心するのです。理にかなっています。超複雑なコンピューターを作ろうと四苦八苦している私たちですが、そのための完璧な見本が私たち一人一人の頭の中にあるのです。

This is the icky part. The truth is, no one really knows how to make it smart—we’re still debating how to make a computer human-level intelligent and capable of knowing what a dog and a weird-written B and a mediocre movie is. But there are a bunch of far-fetched strategies out there and at some point, one of them will work. Here are the three most common strategies I came across:

1) 脳を盗作する

これは、隣の席に座っている頭の良い子がなぜあんなにテストの成績が良いのかを科学者が苦労して解明しようとするようなものです。一生懸命勉強しても、その子には到底及ばない。そして最後には「もういい、その子の答案を写させてもらおう」と決心するのです。理にかなっています。超複雑なコンピューターを作ろうと四苦八苦している私たちですが、そのための完璧な見本が私たち一人一人の頭の中にあるのです。

Plagiarize the brain. This is like scientists toiling over how that kid who sits next to them in class is so smart and keeps doing so well on the tests, and even though they keep studying diligently, they can’t do nearly as well as that kid, and then they finally decide “k fuck it I’m just gonna copy that kid’s answers.” It makes sense—we’re stumped trying to build a super-complex computer, and there happens to be a perfect prototype for one in each of our heads.

科学界は、進化がどのようにしてこれほど素晴らしい脳を作り出したのかを解明すべく、脳のリバースエンジニアリングに力を注いでいます。楽観的な予測では、2030年までにはこれを成し遂げられるとのこと。それができれば、脳がいかに強力かつ効率的に機能しているかの秘密が全て明らかになり、そこからヒントを得て、脳の革新的な仕組みを盗用することができるでしょう。脳を模倣したコンピューターアーキテクチャの一例が、人工ニューラルネットワークです。これは、トランジスタの「ニューロン」のネットワークから始まり、互いに入力と出力で結合されていて、最初は何も知りません。まるで乳児の脳のように。学習の仕方は、手書き文字の認識などのタスクを試みることです。最初は、ニューロンの発火とそれに続く文字の推測はランダムですが、正解だと言われればその答えに至った発火経路の結合が強化され、間違っていると言われればその経路の結合が弱められます。このような試行と フィードバックを多数重ねることで、ネットワークは自ら賢いニューラル経路を形成し、機械はそのタスクに最適化されていくのです。脳の学習方法もこれに似ていますが、より洗練されています。脳の研究が進むにつれ、ニューラル回路を活用する画期的な新しい方法が発見されつつあります。

The science world is working hard on reverse engineering the brain to figure out how evolution made such a rad thing—optimistic estimates say we can do this by 2030. Once we do that, we’ll know all the secrets of how the brain runs so powerfully and efficiently and we can draw inspiration from it and steal its innovations. One example of computer architecture that mimics the brain is the artificial neural network. It starts out as a network of transistor “neurons,” connected to each other with inputs and outputs, and it knows nothing—like an infant brain. The way it “learns” is it tries to do a task, say handwriting recognition, and at first, its neural firings and subsequent guesses at deciphering each letter will be completely random. But when it’s told it got something right, the transistor connections in the firing pathways that happened to create that answer are strengthened; when it’s told it was wrong, those pathways’ connections are weakened. After a lot of this trial and feedback, the network has, by itself, formed smart neural pathways and the machine has become optimized for the task. The brain learns a bit like this but in a more sophisticated way, and as we continue to study the brain, we’re discovering ingenious new ways to take advantage of neural circuitry.

より極端な盗作には、「全脳エミュレーション」と呼ばれる戦略があります。これは、実際の脳を薄切りにしてスキャンし、ソフトウェアで正確な3Dモデルを再構築して、それを強力なコンピュータ上で実装するというものです。そうすれば、脳にできること全てができるコンピューターが手に入ります。あとは学習と情報収集をするだけです。技術者の腕が本当に良ければ、脳のアーキテクチャをコンピュータにアップロードした時点で、人格や記憶まで完璧に再現できるほどの精度で脳をエミュレートできるかもしれません。その脳が亡くなる直前のジムのものだったとしたら、目覚めたコンピュータはジム(?)になるでしょう。これは、堅牢な人間レベルのAGIであり、ジムを想像を絶するほど賢いASIに進化させることができます。ジム自身もそれを非常に喜ぶことでしょう。

More extreme plagiarism involves a strategy called “whole brain emulation,” where the goal is to slice a real brain into thin layers, scan each one, use software to assemble an accurate reconstructed 3-D model, and then implement the model on a powerful computer. We’d then have a computer officially capable of everything the brain is capable of—it would just need to learn and gather information. If engineers get really good, they’d be able to emulate a real brain with such exact accuracy that the brain’s full personality and memory would be intact once the brain architecture has been uploaded to a computer. If the brain belonged to Jim right before he passed away, the computer would now wake up as Jim (?), which would be a robust human-level AGI, and we could now work on turning Jim into an unimaginably smart ASI, which he’d probably be really excited about.

全脳エミュレーションの実現までどれくらいあるのでしょうか? これまでのところ、長さ1mmのプラナリアの脳(ニューロンはわずか302個)のエミュレーションにようやく成功したばかりです。人間の脳には1000億個のニューロンがあります。絶望的なプロジェクトに思えるかもしれませんが、指数関数的な進歩の力を忘れないでください。小さなミミズの脳を征服した今、やがてアリ、そしてネズミと続き、突然これがはるかに現実的に見えてくるでしょう。

How far are we from achieving whole brain emulation? Well so far, we’ve not yet just recently been able to emulate a 1mm-long flatworm brain, which consists of just 302 total neurons. The human brain contains 100 billion. If that makes it seem like a hopeless project, remember the power of exponential progress—now that we’ve conquered the tiny worm brain, an ant might happen before too long, followed by a mouse, and suddenly this will seem much more plausible.

2) 進化にもう一度同じことをやらせる

ただし今回は我々のために 頭の良い子のテストを写すのが難しすぎると判断したら、その子がどうやってテスト勉強をしているかを真似してみるのも手です。

Try to make evolution do what it did before but for us this time.

So if we decide the smart kid’s test is too hard to copy, we can try to copy the way he studies for the tests instead.

ここで分かっていることがあります。脳と同じくらい強力なコンピュータを作ることは可能だということです。私たち自身の脳の進化がその証拠です。そして、もし脳が複雑すぎてエミュレートできないとしたら、代わりに進化をエミュレートしてみるのです。実際、脳をエミュレートできたとしても、それは鳥の羽ばたき運動を真似して飛行機を作ろうとするようなものかもしれません。多くの場合、機械は生物を正確に模倣するのではなく、新鮮な機械指向のアプローチで設計するのが最適なのです。

Here’s something we know. Building a computer as powerful as the brain is possible—our own brain’s evolution is proof. And if the brain is just too complex for us to emulate, we could try to emulate evolution instead. The fact is, even if we can emulate a brain, that might be like trying to build an airplane by copying a bird’s wing-flapping motions—often, machines are best designed using a fresh, machine-oriented approach, not by mimicking biology exactly.

では、進化をシミュレートしてAGIを構築するにはどうすればよいのでしょうか? 「遺伝的アルゴリズム」と呼ばれるこの方法は、次のように機能します。パフォーマンスと評価のプロセスが何度も繰り返されます(生物が生きることで「パフォーマンス」を示し、繁殖できるかどうかで「評価」されるのと同じです)。コンピュータ群がタスクを試み、最も成功したものが互いに交配され、プログラムの半分ずつが新しいコンピュータに統合されます。成功度の低いものは淘汰されます。この自然選択のプロセスを非常に多くの世代にわたって繰り返すことで、より優れたコンピュータが生み出されていきます。課題は、この進化のプロセスを自動で回せるような評価と交配のサイクルを作ることです。

So how can we simulate evolution to build AGI? The method, called “genetic algorithms,” would work something like this: there would be a performance-and-evaluation process that would happen again and again (the same way biological creatures “perform” by living life and are “evaluated” by whether they manage to reproduce or not). A group of computers would try to do tasks, and the most successful ones would be bred with each other by having half of each of their programming merged together into a new computer. The less successful ones would be eliminated. Over many, many iterations, this natural selection process would produce better and better computers. The challenge would be creating an automated evaluation and breeding cycle so this evolution process could run on its own.

進化を真似る欠点は、進化は物事を成し遂げるのに10億年もかかるのに対し、我々は数十年でそれをやろうとしていることです。

しかし、私たちには進化に対して多くの利点があります。第一に、進化には先見の明がなく、ランダムに機能します。有益な突然変異よりも無益な突然変異の方が多く生じますが、私たちはプロセスをコントロールして有益な不具合と的を絞った修正のみによって推進します。第二に、進化は知性を含め、何も目指していません。時には知性の高さに反して環境が選択することもあります(多くのエネルギーを使うため)。一方、私たちは意図的にこの進化のプロセスを知性の向上に向けることができます。第三に、進化は知性を選択するために、細胞がエネルギーを生産する方法を改革するなど、知性を促進するためにさまざまな方法で革新しなければなりませんが、私たちはそのような余分な負担を取り除き、電気などを使用することができます。私たちが進化よりもはるかに速いことは間違いありませんが、これを実行可能な戦略にするために進化を十分に改良できるかどうかはまだ明らかではありません。

The downside of copying evolution is that evolution likes to take a billion years to do things and we want to do this in a few decades.

But we have a lot of advantages over evolution. First, evolution has no foresight and works randomly—it produces more unhelpful mutations than helpful ones, but we would control the process so it would only be driven by beneficial glitches and targeted tweaks. Secondly, evolution doesn’t aim for anything, including intelligence—sometimes an environment might even select against higher intelligence (since it uses a lot of energy). We, on the other hand, could specifically direct this evolutionary process toward increasing intelligence. Third, to select for intelligence, evolution has to innovate in a bunch of other ways to facilitate intelligence—like revamping the ways cells produce energy—when we can remove those extra burdens and use things like electricity. It’s no doubt we’d be much, much faster than evolution—but it’s still not clear whether we’ll be able to improve upon evolution enough to make this a viable strategy.

3)この問題全体をコンピュータの問題にする

私たちの問題ではなく これは、科学者が必死になってテスト自体を受けるようにプログラムしようとするようなものです。しかし、これが最も有望な方法かもしれません。

考え方としては、AIの研究とそれ自身のアーキテクチャを変更するコーディングを主な機能とするコンピュータを作るということです。それにより、学習だけでなく自己改善も可能になります。コンピュータにコンピュータ科学者になってもらい、自らの開発を後押しできるようにするのです。そして、それが彼らの主な仕事になります。つまり、自分自身をどうすればもっと賢くできるかを考えることです。これについては後ほど詳しく説明します。

Make this whole thing the computer’s problem, not ours.

This is when scientists get desperate and try to program the test to take itself. But it might be the most promising method we have.

The idea is that we’d build a computer whose two major skills would be doing research on AI and coding changes into itself—allowing it to not only learn but to improve its own architecture. We’d teach computers to be computer scientists so they could bootstrap their own development. And that would be their main job—figuring out how to make themselves smarter. More on this later.

これらのことがすぐに起こるかもしれない

ハードウェアの急速な進歩とソフトウェアの革新的な実験が同時に起こっており、AGI(人工汎用知能)は主に2つの理由から、急速かつ予期せず私たちに忍び寄ってくる可能性があります。

Rapid advancements in hardware and innovative experimentation with software are happening simultaneously, and AGI could creep up on us quickly and unexpectedly for two main reasons:

1)指数関数的な成長は激しく、進歩のペースがカタツムリのように見えても、すぐに上昇に転じる可能性があります。このGIFがこの概念をうまく表現しています。

Exponential growth is intense and what seems like a snail’s pace of advancement can quickly race upwards—this GIF illustrates this concept nicely:

2) ソフトウェアに関しては、進歩は遅いように見えるかもしれませんが、ひとつの閃きが進歩のスピードを一瞬で変えてしまうことがあります(宇宙が地球中心だと考えられていた時代、科学者たちは宇宙がどのように機能しているのか計算するのに苦労していましたが、宇宙が太陽中心であることが発見されると、突然すべてがはるかに簡単になったようなものです)。あるいは、自己改善するコンピュータのようなものの場合、私たちはまだ遠く離れているように思えるかもしれませんが、実際にはシステムを一度調整するだけで、1,000倍も効果的になり、人間レベルの知性へと一気に上昇する可能性があるのです。

When it comes to software, progress can seem slow, but then one epiphany can instantly change the rate of advancement (kind of like the way science, during the time humans thought the universe was geocentric, was having difficulty calculating how the universe worked, but then the discovery that it was heliocentric suddenly made everything much easier). Or, when it comes to something like a computer that improves itself, we might seem far away but actually be just one tweak of the system away from having it become 1,000 times more effective and zooming upward to human-level intelligence.

AGIからASIへの道のり

いつかは、人間レベルの汎用知能を持つコンピュータ、つまりAGIを実現するでしょう。人間とコンピュータが対等に共存する、そんな世界が訪れるのです。

いえ、実際はそうではありません。

知能レベルや計算能力が人間と同等のAGIであっても、人間に対して大きなアドバンテージを持つことになるのです。例えば、

At some point, we’ll have achieved AGI—computers with human-level general intelligence. Just a bunch of people and computers living together in equality.

Oh actually not at all.

The thing is, AGI with an identical level of intelligence and computational capacity as a human would still have significant advantages over humans. Like:

ハードウェア面では:

スピード。 脳のニューロンは最大でも200Hzですが、今日のマイクロプロセッサ(AGIに到達する頃にはさらに高速化しているでしょう)は2GHzで動作します。これは我々のニューロンの1000万倍の速さです。また、脳内の通信は約120m/sですが、コンピュータは光速で通信できるため、脳より圧倒的に速いのです。

サイズとストレージ。 脳のサイズは頭蓋骨の形状に制限されており、これ以上大きくなることはできません。仮に大きくなったとしても、120m/sの内部通信では脳の構造間の情報伝達に時間がかかりすぎてしまいます。一方、コンピュータは物理的にどんなサイズにも拡張でき、より多くのハードウェアを使用できるほか、より大きなワーキングメモリ(RAM)と、人間よりはるかに大容量かつ精密な長期記憶(ハードドライブストレージ)を持つことができるのです。

信頼性と耐久性。 コンピュータの方が人間の脳より精密なのは、記憶だけではありません。コンピュータのトランジスタは生物学的ニューロンよりも正確で、劣化しにくく(劣化しても修理や交換が可能)、人間の脳は疲れやすいですが、コンピュータは24時間365日休みなく最高のパフォーマンスを発揮し続けられます。

Hardware:

Speed. The brain’s neurons max out at around 200 Hz, while today’s microprocessors (which are much slower than they will be when we reach AGI) run at 2 GHz, or 10 million times faster than our neurons. And the brain’s internal communications, which can move at about 120 m/s, are horribly outmatched by a computer’s ability to communicate optically at the speed of light.

Size and storage. The brain is locked into its size by the shape of our skulls, and it couldn’t get much bigger anyway, or the 120 m/s internal communications would take too long to get from one brain structure to another. Computers can expand to any physical size, allowing far more hardware to be put to work, a much larger working memory (RAM), and a longterm memory (hard drive storage) that has both far greater capacity and precision than our own.

Reliability and durability. It’s not only the memories of a computer that would be more precise. Computer transistors are more accurate than biological neurons, and they’re less likely to deteriorate (and can be repaired or replaced if they do). Human brains also get fatigued easily, while computers can run nonstop, at peak performance, 24/7.

ソフトウェア面では:

編集可能性、アップグレード性、より広い可能性。 人間の脳とは異なり、コンピュータのソフトウェアはアップデートや修正が可能で、簡単に実験できます。また、アップグレードにより、人間の脳が苦手とする分野の能力も向上できます。人間の視覚ソフトウェアは非常に高度ですが、複雑なエンジニアリング能力はかなり低レベルです。コンピュータは人間並みの視覚ソフトウェアを備えつつ、エンジニアリングやその他の分野でも同等に最適化されることができるのです。

集合的能力。 人間は他のどの種よりも優れた集合知性を構築できますが、言語の発達と大規模・高密度コミュニティの形成から始まり、文字と印刷の発明を経て、インターネットなどのツールによってさらに強化された人類の集合知性は、他の種を大きく引き離した主な理由の一つです。そしてコンピュータは、この点で私たち人間をはるかに上回ります。特定のプログラムを実行する世界規模のAIネットワークは、定期的に同期することで、あるコンピュータが学習したことを瞬時に他のすべてのコンピュータにアップロードできます。また、人間社会のような反対意見や動機、私利私欲がないため、グループは一つの目標に向かって一丸となって取り組むことができるのです。

Software:

Editability, upgradability, and a wider breadth of possibility. Unlike the human brain, computer software can receive updates and fixes and can be easily experimented on. The upgrades could also span to areas where human brains are weak. Human vision software is superbly advanced, while its complex engineering capability is pretty low-grade. Computers could match the human on vision software but could also become equally optimized in engineering and any other area.

Collective capability. Humans crush all other species at building a vast collective intelligence. Beginning with the development of language and the forming of large, dense communities, advancing through the inventions of writing and printing, and now intensified through tools like the internet, humanity’s collective intelligence is one of the major reasons we’ve been able to get so far ahead of all other species. And computers will be way better at it than we are. A worldwide network of AI running a particular program could regularly sync with itself so that anything any one computer learned would be instantly uploaded to all other computers. The group could also take on one goal as a unit, because there wouldn’t necessarily be dissenting opinions and motivations and self-interest, like we have within the human population.10

自己改善するようプログラムされることでAGIに到達すると思われるAIは、「人間レベルの知能」を重要な節目とは捉えず(それは私たち人間の視点からの指標に過ぎません)、人間のレベルで「停止」する理由もないでしょう。人間と同等の知能を持つAGIですら人間に対して優位であることは明らかなので、人間の知性に到達した瞬間から、人間を超える知性の領域に向かって一直線に進化していくはずです。

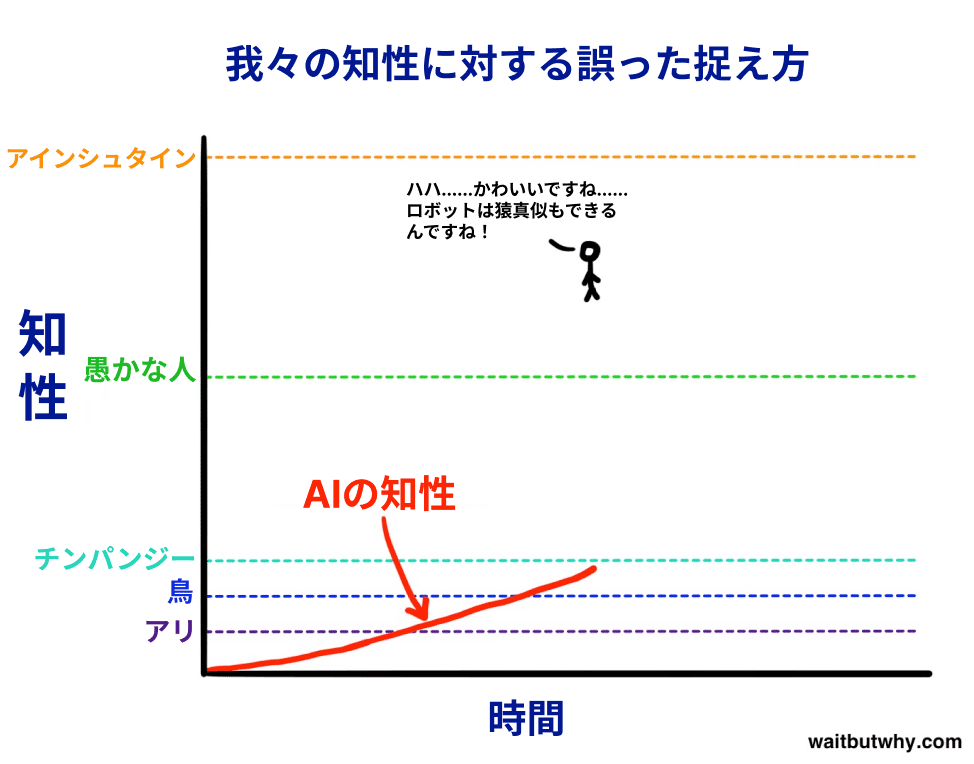

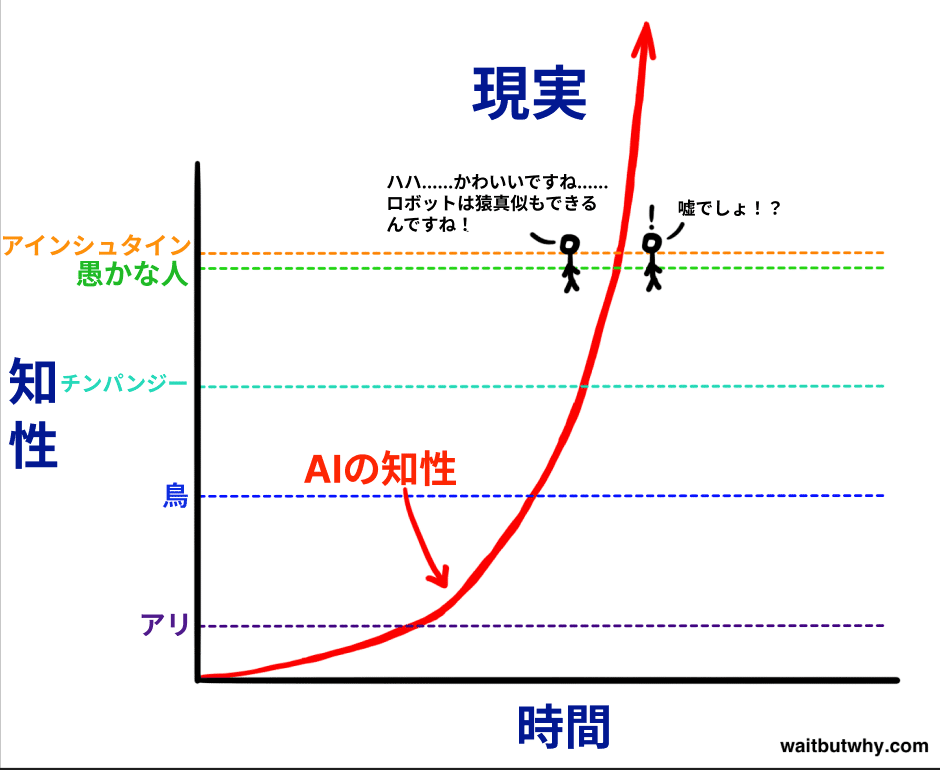

これが起こった時、私たちは驚愕するかもしれません。その理由は、私たちの視点からすると、A)動物の知能はそれぞれ異なるものの、どの動物の知能も人間よりはるかに劣っているという点では共通しており、B)最も賢い人間は、最も賢くない人間よりも格段に賢いと考えているからです。こんな感じでしょうか。

AI, which will likely get to AGI by being programmed to self-improve, wouldn’t see “human-level intelligence” as some important milestone—it’s only a relevant marker from our point of view—and wouldn’t have any reason to “stop” at our level. And given the advantages over us that even human intelligence-equivalent AGI would have, it’s pretty obvious that it would only hit human intelligence for a brief instant before racing onwards to the realm of superior-to-human intelligence.

This may shock the shit out of us when it happens. The reason is that from our perspective, A) while the intelligence of different kinds of animals varies, the main characteristic we’re aware of about any animal’s intelligence is that it’s far lower than ours, and B) we view the smartest humans as WAY smarter than the dumbest humans. Kind of like this:

そして、AIの知性が私たちに向かって急上昇するにつれ、私たちは単にAIが動物としてより賢くなっていると捉えるでしょう。そして、AIが人類の最低レベルの知能、ニック・ボストロムが「村の馬鹿者」と呼ぶレベルに到達すると、私たちは「おやおや、まるで馬鹿な人間のようだ。可愛いね!」と思うはずです。しかし実際には、知性の大きなスペクトラムの中で、村の馬鹿者からアインシュタインまで、全ての人間はごく狭い範囲に収まっているのです。つまり、村の馬鹿者レベルに到達してAGIであると宣言された直後、AIは突如アインシュタインよりも賢くなり、私たちは何が起こったのかわからなくなってしまうのです。

このグラフのように、人間の知性の幅は非常に狭いため、AIがAGIに到達した瞬間、すぐに人間を超える知性を持つことになります。そしてその後も、私たちが想像もできないようなスピードで、AIの知性は加速度的に進化を続けるのです。

私たちから見ると、動物はゆっくりと進化しているように見えますが、AIの知性の急成長はそれとは全く異なります。AIはあっという間に人間の知性を追い抜き、さらに超人的な知性の領域へと突き進んでいくのです。

So as AI zooms upward in intelligence toward us, we’ll see it as simply becoming smarter, for an animal. Then, when it hits the lowest capacity of humanity—Nick Bostrom uses the term “the village idiot”—we’ll be like, “Oh wow, it’s like a dumb human. Cute!” The only thing is, in the grand spectrum of intelligence, all humans, from the village idiot to Einstein, are within a very small range—so just after hitting village idiot level and being declared to be AGI, it’ll suddenly be smarter than Einstein and we won’t know what hit us:

そして、その先には...?

知性の爆発

ここからは、この話題が異常で怖いものになります。そしてこれからもずっとそうなのです。ここで一度、私が言おうとしていることは全て、最も尊敬されている多くの思想家や科学者たちによる本物の科学と未来予測であることを思い出してください。

I hope you enjoyed normal time, because this is when this topic gets unnormal and scary, and it’s gonna stay that way from here forward. I want to pause here to remind you that every single thing I’m going to say is real—real science and real forecasts of the future from a large array of the most respected thinkers and scientists. Just keep remembering that.

さて、先に述べたように、AGIに到達するための現在のモデルのほとんどは、AIが自己改善によってそこに到達するというものです。そしてAGIに到達すると、自己改善を伴わない方法で形成され成長したシステムであっても、自ら望めば自己改善を始めるのに十分な知性を持つようになります。

Anyway, as I said above, most of our current models for getting to AGI involve the AI getting there by self-improvement. And once it gets to AGI, even systems that formed and grew through methods that didn’t involve self-improvement would now be smart enough to begin self-improving if they wanted to.3

そしてここで、「再帰的自己改善」という強烈な概念に行き着きます。これは次のように機能します。

ある程度のレベル(たとえば人間の馬鹿者レベル)のAIシステムが、自らの知性を向上させる目標でプログラムされます。一度それを行うと、AIはより賢くなり(たとえばアインシュタインのレベルになります)、アインシュタインレベルの知性で知性の向上に取り組むため、より簡単に、より大きな飛躍ができるようになります。この飛躍により、AIはどんな人間よりもはるかに賢くなり、さらに大きな飛躍ができるようになるのです。飛躍がより大きくなり、より急速に起こるようになると、AGIの知性は急上昇し、まもなく超人的なASIシステムのレベルに到達します。これは「知性の爆発」と呼ばれ、「加速する変化の法則」の究極の例なのです。

And here’s where we get to an intense concept: recursive self-improvement. It works like this—

An AI system at a certain level—let’s say human village idiot—is programmed with the goal of improving its own intelligence. Once it does, it’s smarter—maybe at this point it’s at Einstein’s level—so now when it works to improve its intelligence, with an Einstein-level intellect, it has an easier time and it can make bigger leaps. These leaps make it much smarter than any human, allowing it to make even bigger leaps. As the leaps grow larger and happen more rapidly, the AGI soars upwards in intelligence and soon reaches the superintelligent level of an ASI system. This is called an Intelligence Explosion,11 and it’s the ultimate example of The Law of Accelerating Returns.

AIがいつ人間レベルの汎用知能に到達するかについては議論がありますが、AGIに到達する可能性が50%を超える年について数百人の科学者を対象に行った調査の中央値は2040年でした。これは今から25年後に過ぎませんが、この分野の多くの思想家は、AGIからASIへの進化が非常に速く起こる可能性が高いと考えています。例えば、こんなことが起こるかもしれません。

There is some debate about how soon AI will reach human-level general intelligence. The median year on a survey of hundreds of scientists about when they believed we’d be more likely than not to have reached AGI was 204012—that’s only 25 years from now, which doesn’t sound that huge until you consider that many of the thinkers in this field think it’s likely that the progression from AGI to ASI happens very quickly. Like—this could happen:

最初のAIシステムが低レベルの汎用知能に到達するまでに数十年かかりますが、ついにそれが実現します。コンピュータは4歳の人間と同じように周囲の世界を理解できるようになるのです。その瞬間から1時間以内に、そのシステムは一般相対性理論と量子力学を統一する物理学の大理論を生み出します。それは人間には決定的にできなかったことです。そこからさらに90分後、AIはASIになり、人間の170,000倍の知性を持つようになります。

It takes decades for the first AI system to reach low-level general intelligence, but it finally happens. A computer is able to understand the world around it as well as a human four-year-old. Suddenly, within an hour of hitting that milestone, the system pumps out the grand theory of physics that unifies general relativity and quantum mechanics, something no human has been able to definitively do. 90 minutes after that, the AI has become an ASI, 170,000 times more intelligent than a human.

そのような規模の超知性は、私たちにはまったく理解できないものです。マルハナバチがケインズ経済学を理解できないのと同じです。私たちの世界では、賢いとはIQ130、愚かとはIQ85を意味します。IQ12,952という言葉はありません。

Superintelligence of that magnitude is not something we can remotely grasp, any more than a bumblebee can wrap its head around Keynesian Economics. In our world, smart means a 130 IQ and stupid means an 85 IQ—we don’t have a word for an IQ of 12,952.

私たちが知っているのは、人間のこの地球における完全な支配は、「知性とともに力が存在する」という明確なルールを示唆しているということです。つまり、ASIは、私たちがそれを創造したとき、地球上の生命の歴史の中で最も強力な存在となり、人間を含むすべての生命は、完全にその気まぐれに左右されることになります。そしてこれは、今後数十年の間に起こるかもしれないのです。

What we do know is that humans’ utter dominance on this Earth suggests a clear rule: with intelligence comes power. Which means an ASI, when we create it, will be the most powerful being in the history of life on Earth, and all living things, including humans, will be entirely at its whim—and this might happen in the next few decades.

私たちの貧弱な脳がWi-Fiを発明できたのなら、私たちの100倍、1,000倍、10億倍も賢い何かが、いつでも好きなように世界中の一つ一つの原子の位置を制御することは、私たちが電気をつけるようなささいなことのはずです。人間の老化を逆転させる技術の創造、病気や飢餓、さらには死の克服、地球上の生命の未来を守るための気象の再プログラミング。これらすべてが突然可能になるのです。また、地球上のすべての生命の即時の終焉も可能になります。私たちに関する限り、ASIが存在するようになれば、地球上に全能の神が存在することになります。そして私たちにとって最も重要な問題は次のようなものです。

If our meager brains were able to invent wifi, then something 100 or 1,000 or 1 billion times smarter than we are should have no problem controlling the positioning of each and every atom in the world in any way it likes, at any time—everything we consider magic, every power we imagine a supreme God to have will be as mundane an activity for the ASI as flipping on a light switch is for us. Creating the technology to reverse human aging, curing disease and hunger and even mortality, reprogramming the weather to protect the future of life on Earth—all suddenly possible. Also possible is the immediate end of all life on Earth. As far as we’re concerned, if an ASI comes to being, there is now an omnipotent God on Earth—and the all-important question for us is:

それは良い神様になるのでしょうか?

パート2へ続きます…

いかがだったでしょうか?この度は、waitbutwhyの記事「AI革命:超知能への道のり|The AI Revolution: The Road to Superintelligence」の日本語版(パート1)をお届けしました。この記事が皆さんに、AIの未来に関する新たな視点や洞察を提供できたことを願っています。waitbutwhyの著者にも感謝の意を表したいと思います。

しかしこれで終わりではありません。実は、この記事にはパート2があり、パート2でも引き続き興味深い議論が展開されています。ぜひ、次回のパート2も楽しみにしていただき、一緒にAIに関する議論や知識を深め、未来の可能性について考えることができればと思います。

また、waitbutwhyのオリジナル記事にもアクセスし、より多くの情報や議論を楽しんでいただければ幸いです。皆さんの意見や感想もお待ちしておりますので、ぜひコメント欄でシェアしてください。

これからも継続的に ChatGPT/AI 関連の情報について発信していきますので、フォロー (@ctgptlb)よろしくお願いします。この革命的な技術の最先端を共に体験しましょう!

元記事